Why behind AI: State of AI report (Part 2)

This week we continue the deep dive into The State of AI report, which compiles most of the key research and progress over the past year, providing a big-picture overview of the industry. The focus for this week is on the industry and their predictions.

There was a big shift in communication in the last 12 months, as the frontier labs started talking more about "superintelligence" than AGI. There are different ways to interpret this, some cynical (allows us to raise more money), some practical (AGI as defined historically has been achieved but it's inconvenient for OpenAI and Microsoft for legal reasons), some concerningly bullish (the leading researchers believe sentient AI that's significantly more capable than us will be created within a few years due to scaling laws).

Assuming such powerful AI models are possible, the practical challenges of acquiring the compute, deploying it, and powering it are nothing short of staggering. While the core thesis is that superintelligence will reshape our world, the practical reality is that we probably will have to do that prior to actually getting there.

The build out is necessary not just because of the need to train new models, but also to serve the massively increased inference needs. Keeping in mind that capabilities keep increasing, while cost has significantly reduced relative to the level of intelligence the models provide, the demand for inference seems to keep accelerating.

Companies that base their value proposition on AI and operate internally with an AI-native tech stack are growing at significantly faster rates than how SaaS performed historically. The pace of growth is even more incredible if we account for the fact that SaaS peaked during the COVID bubble and many of the companies we consider "rocketships" of the pre-2023 era look almost like laggards from today's point of view.

Some of the most reliable data we have is simply based on spending patterns, i.e. where B2B dollars are going. Based on the figures seen by Stripe and Ramp, it's clear that the growth announcements by AI-first vendors mostly map against the actual spending patterns seen in a selection of their customers. There is an obvious gap here: selection bias (i.e. companies that run on Ramp or Stripe for their payment infrastructure are more likely to also adopt other AI-powered tools), but this is normal at a stage of the market where we are still talking about early adopters as the key demographic.

We can also see that the inference business from the hyperscalers, who are serving the middle and laggard cohorts of customers, has also seen exceptional growth, with Azure serving close to a $13B run-rate in AI inference.

One of the most repeated bear arguments against the industry is that the majority of players make no margins on their products. There are some structural issues with those arguments.

The first key element to understand is that each training run for a significant new model release has a certain cost-revenue profile. While somebody like Buffett would never want to invest in businesses that require significant capex in order to remain competitive, the reality is that in software, profitability only became a topic during the cloud optimization years. The majority of hypergrowth SaaS companies lost significant amounts of money in their growth phases, which investors were happy to be compensated for with rising stock prices. This dynamic looks completely different today, partly because none of the frontier labs is anywhere close to going public (or is actually interested in it), and also because these investments are mostly going into compute, rather than headcount and marketing expenses as during the peak SaaS era.

Since the investment is going into compute, then a more fair way of understanding the frontier labs' business models is based on whether they are reaching reasonable margins and profitability from their existing training runs, which appears to be the case. So the businesses are sustainable, as long as they can turn a profit on each new training run or have enough buffer to absorb the impact when they are not able to deliver an improved product.

So then the margins argument makes a lot more sense for the new businesses that are building on top of the frontier labs' APIs. Here the conversation gets more nuanced since the whole history of SaaS is arguably somebody building wrappers around core infrastructure (such as AWS). The viability of the AI-first companies will depend on their capability of offering a differentiated product, and it's not surprising that many are not finding this PMF yet. This is also an opportunity for existing incumbents to play into this area and benefit from other network effects, as we've seen with SAP and their focus on building AI applications on top of the essentially unexportable data.

A lot of this inference is driven by the move from regular search towards AI search within relevant applications. The different frontier labs have offered a variety of tools to do regular searches (including agentic/computer use behavior), while companies like Perplexity have been able to establish themselves as a viable option for early adopters willing to pay for specialized software. This is probably the most underreported trend in the industry today, as retailers have built their storefronts around humans exploring and shopping. "Entity" visits or even just API access is a completely different experience to optimize for and much more difficult to be competitive at. It's not surprising that OpenAI recently launched applications with ChatGPT itself, giving companies the option to still have some control over the customer experience.

So if inference continues to scale, the frontier labs have been able to demonstrate PMF and path to growth to their investors, and “wrapper” companies are scaling significantly, what’s the logical step?

Focus on the core infrastructure that powers everything.

While Oracle clearly has been able to capture a lot of attention due to their work with OpenAI, the reality is that the build out of AI infrastructure is such a massive undertaking across the chain that it has become a "sport of kings". There will be no "innovative startups" disrupting the infra layer.

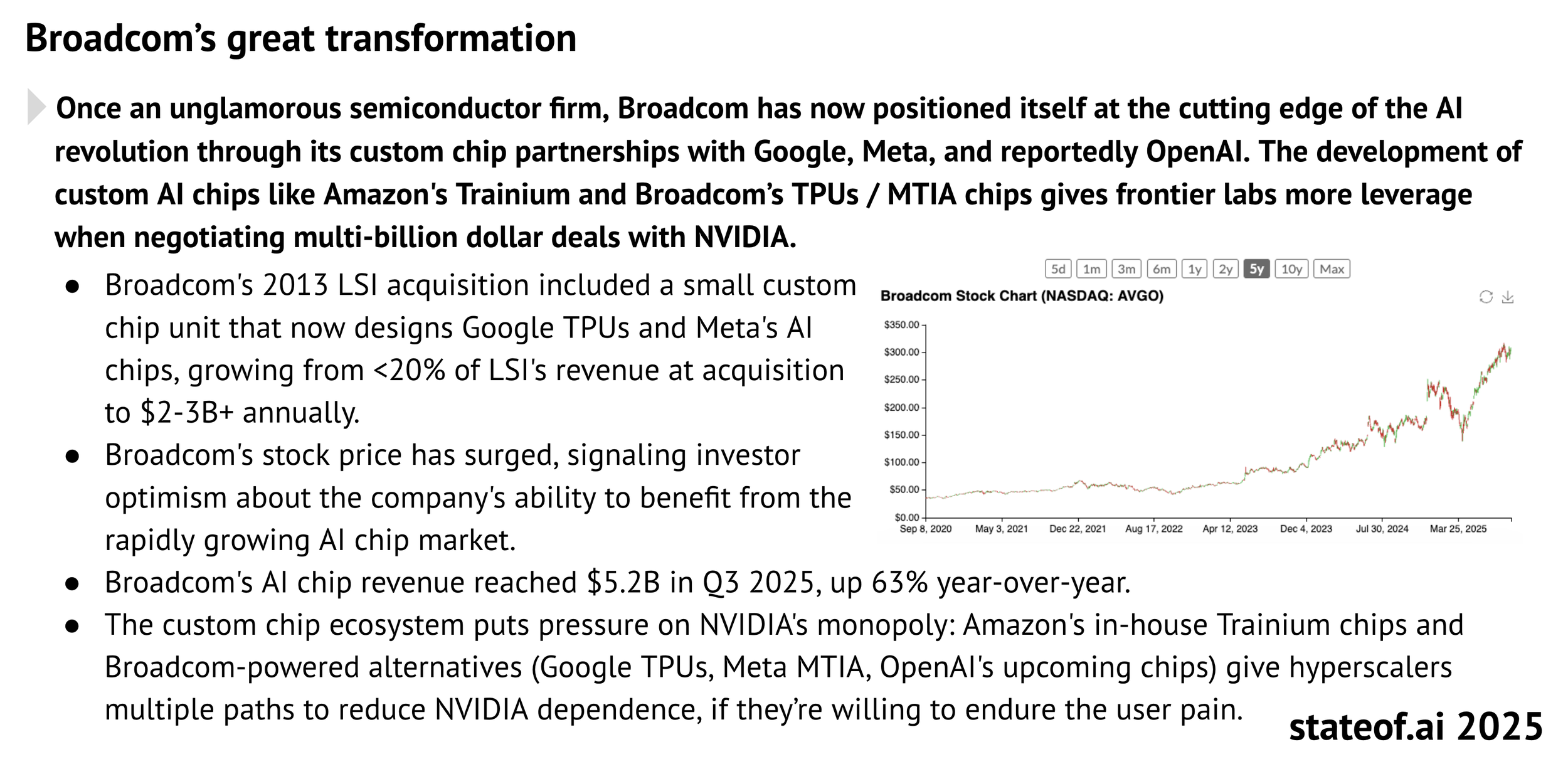

One of the biggest winners behind the scenes has been Broadcom, which has taken a significant role in building out custom hardware based on the needs of the frontier labs. While it's debatable whether this actually gives them an edge or if it's simply a diversification play, the 3x of their stock in the last two years speaks for itself.

These chips (together with the large buyouts of NVIDIA compute capacity) are going towards multiple large clusters that the frontier labs are building (with Colossus having scaled to 100k chips previously, aiming for close to 550k by the end of 2026).

Every 1GW of build-out costs a lot. $50B in capex covers approximately five years of useful utilization, assuming no outside interference with the cluster (such as crippling cyberattacks or physical sabotage).

Currently, the reality is that the US dominates both training and inference capacity. There has been an aggressive effort across multiple players to maintain the lead, together with consistent export controls and technological lead in utilizing EUV-printed chips (i.e. high efficiency and more compute per W). The other side of the coin, however…

In 2024, both China and the US set records for peak electricity demand, 1,450 GW and 759 GW respectively. While China must serve more demand, it is also building a larger overhang of available power. In China, reserve margins are beginning to exceed those cited in the US, meaning larger buffers that can accommodate new load. In line with this trend, China’s thermal fleet operates further below maximum capacity than its counterpart in the US. Similarly, as more renewable capacity comes online in China, curtailment rates outpace those in America. While congestion can cause issues, it also suggests Chinese solar and wind projects are underutilized and could be redirected toward new data centers.

The US does maintain certain advantages. Outages are less frequent in the US; whereas interruptions can occur in China due to fluctuations in the price of coal, potentially hurting the reliability of certain data centers. Also, the average cost of electricity for data centers in the US is lower, yet this can vary considerably by state or province. The US grid also produces considerably less emissions per kWh.

The fact that a country with four times the population and home to the majority of industrial manufacturing today requires more power is not surprising. The fact that it's scaling that electric grid so quickly, even if it is making significant trade-offs, is the biggest reason for concern in the context of AI.

At a high level, the reason why NVIDIA is having exceptional growth even today is because each new generation of their compute is significantly more efficient and scales better, i.e. the same server rack on a new architecture is as productive as three racks from the generation just last year.

The assumption is that if we keep deploying this advanced compute in the West, while China is stuck producing homegrown chips that are much more inefficient, we will get to AGI first.

The problem that western companies have is that we don't know how much compute we need to get there. Scaling with compute still works, so we will keep adding more. However, whether it will take another 10 GW of the most advanced chips or 10,000 GW, that's just speculation. Particularly, since with the current tempo, the USA will simply not be able to add sufficient electric grid capacity to keep playing the game.

On the other side of the world, China is sitting on massive amounts of electricity and they will only keep adding to it. So unlike the USA, they can actually sustain the grid demands, but whether they actually have the appetite to invest at that level is unclear. As covered in my Alibaba Cloud article, they are making a $52B investment over three years in AI infrastructure and development. The trick is that this would barely pay for 1GW of compute. A more cynical point of view might be that you don't need to pay for the research required to get to AGI when you can simply ensure you have sufficient inference and steal the model weights once the other side gets there.

The more balanced take would be that governments do not actually care whether AGI or superintelligence is possible, they simply want to ensure that the basic public good of AI inference is possible domestically.

NVIDIA has been a big proponent of the concept of Sovereign AI, and Jensen has been advocating for it in multiple in-person meetings with heads of state. This has expanded their addressable market a little bit, but the reality is that 75% of all revenue comes from US frontier labs, hyperscalers operating on their behalf, or infra middlemen like Oracle and Coreweave.

Interestingly enough, the funding for this is not actually coming only from existing revenues and the public. More than 25% of the investment in AI cloud infrastructure came from Middle Eastern players.

At the end of the day, the value of AI is accruing at the bottom of the stack and nobody has benefited as much as NVIDIA. While investing in alternatives has brought returns, simply banking on NVIDIA along the ride in the same period was dramatically more lucrative.

Which brings us to the big question: what's next for AI? Here are some predictions from the report:

My view on these:

Almost guaranteed.

Unless Meta decided to play the game again with Llama or we count open-sourcing Grok 4 as one of those, the reality is that outside of some startups like Reflection AI, nobody wants to waste resources on open-source models.

Realistic, low 30s probability.

Probably already happening behind closed doors (I can't say more, but directionally likely).

Not yet, not enough compute is allocated to these.

Don't see why the US would play along.

Very likely.

Realistic, low 40s probability and only for a short time.

If the cost of electricity keeps going up, very likely it will be a significant topic for the midterms.

Probably too short a time frame for something like this to play out. SCOTUS takes years.

The best/worst part, depending on your frame of mind, is that there will probably be at least five other things that happen and are a lot more consequential.