Why behind AI: State of AI report (Part 1)

In the next two weeks, we’ll take a look at The State of AI report, which compiles most of the key research and progress over the past year, providing a big-picture overview of the industry. Their predictions tend to happen more often than not, making this even more relevant as we gear up for another massive year of adoption.

It’s difficult to overstate the impact that reasoning had on the industry, both in terms of the leap in capabilities and the overall consumption of tokens.

Every major frontier model today has a reasoning version, and it typically benchmarks significantly higher than the alternatives it serves. The launch of GPT-5 also revealed a very peculiar statistic: that only 7% of ChatGPT Plus users have actually used a reasoning model since the launch of o1. This was quite shocking due to the massive adoption of reasoning models across the early-adopter space, which was aggressively monetized through Claude Code and subscriptions with added compute benefits. A big difference this year was also the launch of very heavy reasoning models such as o3/GPT-5 Pro, Gemini Deep Think, and Grok Heavy.

I’ve discussed extensively how my very bullish views on AI stem essentially from my daily use of pro models and coding agents via terminal (which tend to perform better than the web-client versions). When you see takes online about “no value in AI” and “failed implementations,” it’s important to calibrate with the fact that, just for white-collar work (i.e., researching topics, making decisions with outsized outcomes, and analyzing data), the most expensive reasoning models are better than the majority of individuals you’ll work with.

I think that from these, the two that are interesting to call out are the prediction that an open-source model actually had a chance to overtake o1 from a benchmarking perspective and that Apple would be able to capture demand for on-device AI. The two are interestingly correlated, since if open-source models progressed strongly, there was going to be a logical downstream effect on having smaller models that are suitable for on-device inference.

While DeepSeek did become a significant early win for open-source AI at the start of the year, this did not sustain. The best models in the industry today are all trained by frontier labs, and the gaps are getting bigger. There is intention to counteract that both with heavy investments from Alibaba, as well as new players like Reflection AI that are raising funds to train new models, but right now this still appears to be a very difficult lead to catch.

Apple famously fumbled their on-device inference launch by training and running models that were just not particularly good, which led to poor performance in the features ahead of their official launch. Other large players have had similar issues with their internal efforts, with Salesforce recently announcing a large deal with OpenAI after two years of talking about their “Enterprise AI advantage with internal models.” It appears that the gap between expertise in ML alone (which has been a strong point historically for Apple) has not translated easily into the same type of knowledge transfer to LLMs. Most probably this is related less so with the language part of training the models and more with the fact that none of the current frontier labs is actually delivering LLMs alone; they offer services that are built with a lot of scaffolding around the LLMs. I refer to Claude Code often as a great example of a product precisely because it’s not just Sonnet 4.5 via API, but is able to interact with other applications (tool calling) and execute code by itself. These are not “baked in” capabilities in the LLM but additional scaffolding that the models are trained on to interact with, without real guarantees that they’ll be able to execute these commands. Grok 4 was quite heavily trained on tool calling but was one of the worst performing models on it because this stuff is hard, really hard.

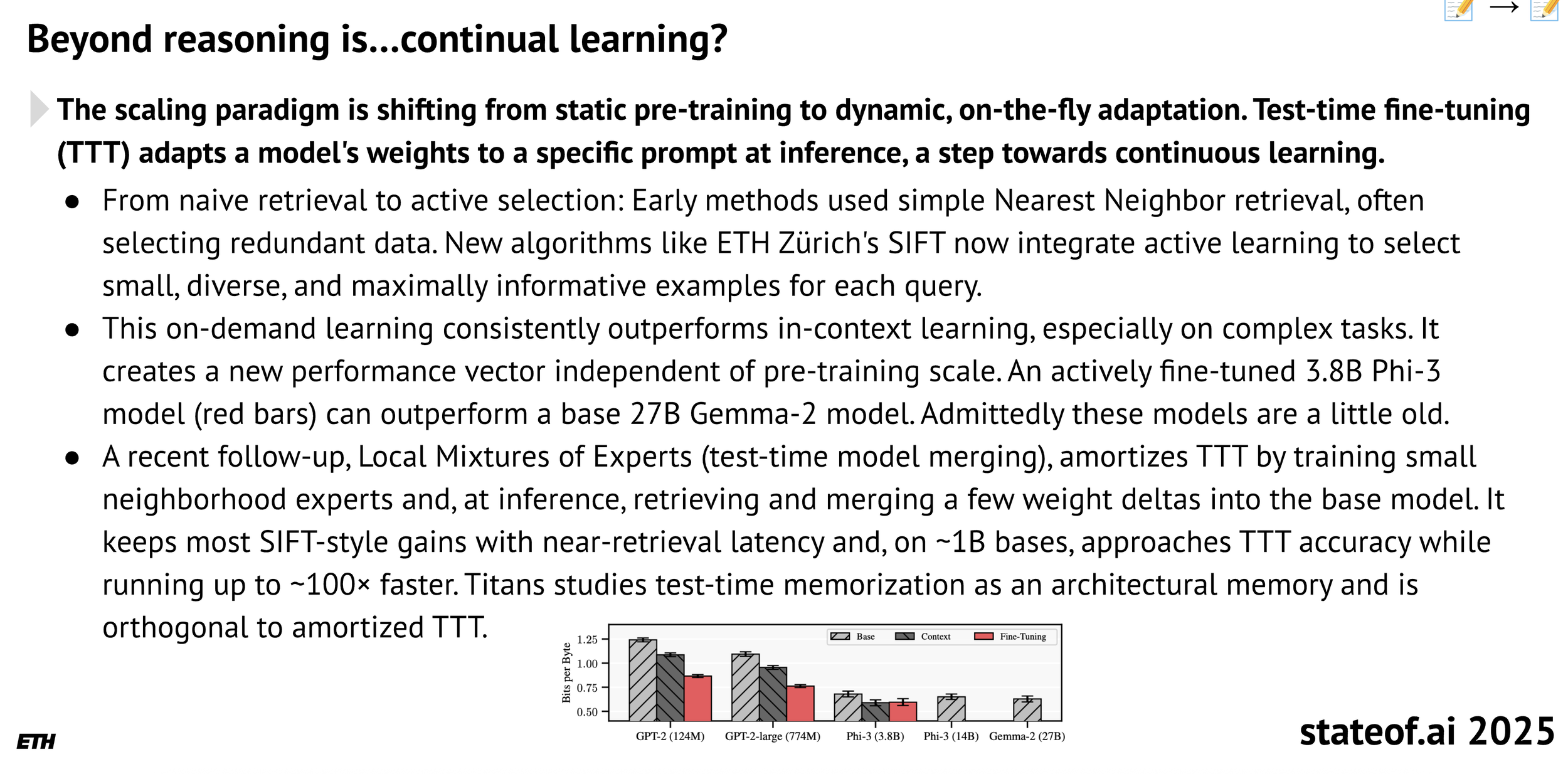

One of the biggest advances this year was for frontier labs to devote substantial compute resources to initial pre-training runs—which enable models to acquire a broad range of capabilities—followed by extensive post-training reinforcement learning to boost accuracy on specific topics. Currently, RL is seen as one of the fastest paths to making models excel at specialized tasks while retaining general capabilities, including executing tasks and solving problems they weren't explicitly trained on.

This doesn’t mean that we’ve easily “solved” specialization, as demonstrated by the very difficult rollout of agentic AI across enterprise applications.

The biggest gap in enterprise AI applications is memory, particularly in enabling agents to learn on the job for specific assigned tasks. Currently, we rely heavily on scaffolding to work around this constraint, but that approach is not sustainable long-term for the applications that will define the new era of productivity. Continual learning is now emerging as one of the hardest problems that researchers aim to solve.

While most in tech do not care about the political aspects of AI, it’s difficult to ignore the elephant in the room: that both the current and future capabilities of LLMs have led to massive capital investments and, with those, government attention. I’ve written on this, but many expect that we will end up with the frontier labs being either nationalized or “strongly supported” from a security perspective.

The charts here are a bit deceptive, as they don’t properly break down actual Hugging Face downloads by country. Recent sentiment on X suggests that the strongest adoption of Qwen or DeepSeek outside of China is in India, which impacts these rankings due to the significant IT infrastructure there. The U.S. vs. China global realignment is happening across both geopolitics and AI; however, most are not paying enough attention to the fact that the “western side” is really limited today to the U.S. and its satellite countries on the European continent, rather than having an actual global reach. If the hyperscalers were releasing proper breakdowns for AI inference sold per country, the results would probably be shocking to many.

Hugging Face is the “primary” space where new open-source models are released, but more importantly, where developers and researchers select existing models and build on top of them. Back in early 2024, Chinese models represented less than 25% of those derivatives, with Meta’s Llama considered “the default.”

Today, things look quite different, with the majority of new fine-tuning activity being done on top of Qwen and DeepSeek. The obvious question is how many of these forks of existing models make it into enterprise applications (very few).

Coming back to the problem of long-term memory for applications, there have been several very interesting video-generation models, such as DeepMind’s Genie 3 and OpenAI’s Sora 2, that demonstrate a significant leap in capabilities for generating real world looking assets, but more importantly, for building persistent worlds based on what's generated. This could essentially allow us to create training simulators that account for all possible variables, from which agents could learn new skills post-training and during deployment.

By drawing parallels to the process of scientific discovery, we could develop “evolutionary” coding agents capable of true creativity. If this approach scales, the obvious pivot, i.e. applying vast amounts of compute to scientific discovery, becomes viable.

We've already seen a version of this play out with protein synthesis via AlphaFold 3, which built on the foundational work that earned DeepMind’s team the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. However, we still need significant progress in this area because AlphaFold's performance heavily depends on the protein's attributes being familiar to the model from its training data. Brand-new and complex chemical discovery requires a very different approach, so advancing other research areas is not as simple as “AlphaFold for X.”

Some of the most interesting progress in the past year came from Tesla and Waymo, rather than traditional research labs or independent researchers. As both companies launched fully self-driving services across several U.S. cities, with Waymo announcing plans today to expand to London in 2026. It appears that real-world applied AI with massive variance in outcomes is being tested at an unprecedented rate.

From an enterprise perspective, the rapid adoption of coding agents has made MCP servers a prominent point of adoption across most vendors. This enabled many companies with limited capabilities and time to easily connect their datasets to their preferred LLMs, bypassing the need to experiment with complex data integrations for AI applications.

If MCP servers brought simplicity and clarity to developers, building agentic workflows has mostly been an exercise in pain, luck, and deep competence. Many players have launched their own implementation frameworks to simplify this process, with DSPy arguably being the most practical for enforcing scaffolding and expected behaviors on unpredictable models. As of today, there isn’t an obvious way to build agentic workflows for most use cases; rather, different tools and ideas work best for different requirements.

This is reflected in the research field as well, with thousands of papers being published on different aspects of building, evaluating, and deploying agents. While this might feel overwhelming, it’s important to note that there is a reason for this concentrated effort across the millions of individuals working in AI today (the value proposition of effective agents is enormous).

Next week, I’ll cover the rest of the report, focused on the industry, politics and their predictions for the next 12 months.